How to Memorize Wes Kao's Advice on Giving Feedback

Mnemonic techniques for internalizing her Substack post, "7 phrases I use to make giving feedback easier for myself"

You're in the meeting. Your colleague just suggested a solution that misses some key considerations. You know you need to give feedback, but your mind goes blank. Will I sound dismissive? Will they think I don't value their input? You remember reading

’s “7 phrases I use to make giving feedback easier for myself”, but what were they again? You end up saying something clunky that lands wrong, and you leave the meeting wishing you'd handled it better.Does that sound familiar or am I the only one? Are you tired of reading on how to become a better communicator but forgetting the advice at the moment you need it most? In today’s post, I will share some practical mnemonic techniques you can use to memorize her recommended phrases, and provide a mental framework to help you quickly retrieve them in your future meetings.

Phrase: “At the same time”

Out of all the phrases she shared, the one that I find myself turning to most is at “at the same time.” I sometimes struggle with exactly how to give feedback, so having go-to phrases helps. The first time I used it in a meeting, I thought: “Wow, this actually works!' So now, let's consider why it works so well.

argued that in certain contexts it is better to use “at the same time” instead of “but” for the following reasons:“But” is a negating word. It cancels out whatever comes before it.

Technically, this isn’t positive or negative—it simply is. It’s neutral. “But” can have a negative undertone though, so if you want to avoid it…

Use “at the same time.”

“At the same time” allows you to mention two potentially competing realities, without discrediting either one. This is helpful when you want to disagree without seeming disagreeable.

🚫 “This idea works well for our current situation, but not for what we need going forward.”

✅ “This idea works well for our current situation. At the same time, going forward we will deal with new variables A and B, which makes me think we may want to consider [alternative option] too.”

PART I: How to Memorize the Phrases

Choose a few key words to memorize from the phrase.

🚫AT the SAME TIME

✅ AT the same TIME

You don't need to memorize every single word of a phrase because your mind automatically fills in the blanks. For example, when I say "MICKEY _______", you think "MOUSE." When I say "JURASSIC ______", your mind completes it with "PARK."

This same principle works with any familiar phrase. If you memorize just "AT" and "TIME", your brain will naturally fill in the middle with "THE SAME" when you see "AT __ __ TIME.

Create an image for the key words.

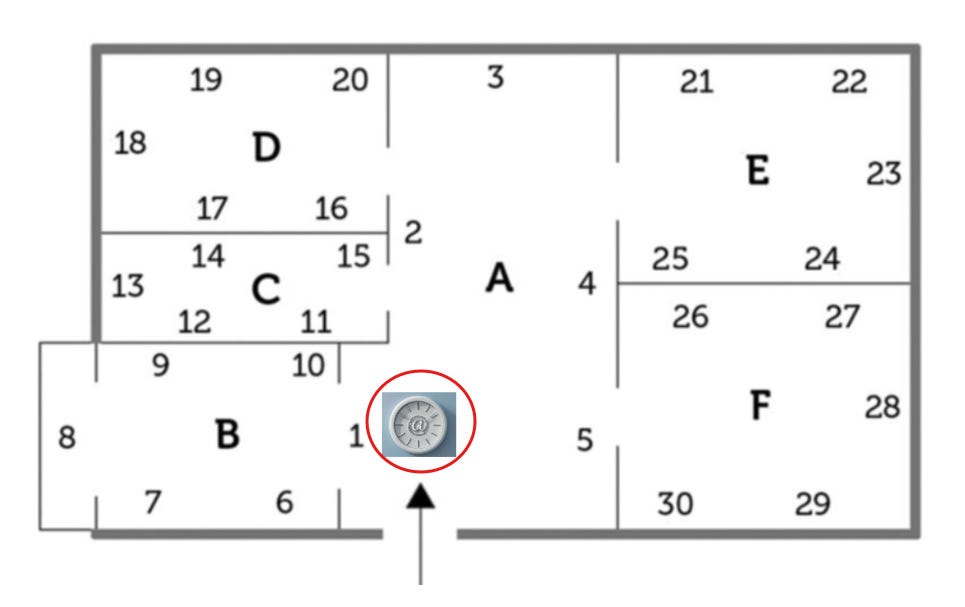

So, now we need to create an image for “at” and “time.” When I hear the word “at,” I automatically picture the “@” symbol from email addresses. Similarly, the word “time” makes me visualize a clock. We can reduce cognitive load by merging these two into one by imagining a clock with an “@” symbol in the center.

Choose a familiar location to store the phrases.

Choose a familiar location, it can be your university campus, a local park, your childhood home, your office building, a relative’s house, etc. (see How to Build a Memory Palace). Then identify 7 locations to store Kao's recommended phrases. If you have chosen a place, I want you to close your eyes, walk to your first location and see the clock sitting there with your mental eye. Pick it up with your hands, feel its texture, sense its weight, and observe its shape. This image that you are holding will act as a representation of the phrase.

Door (“at the same time” / clock)

Couch

TV

Table

Bookshelf

Plant

Window

Create a memorable interaction between the image and location.

It is not enough to simply see the clock at a location, there must be a memorable interaction between the image and the place. According to memory expert Lance Tschirhart, you should be able to look at the location and infer the image of the clock.

Make it unforgettable. If your location is a door, imagine a melted clock, like those in Salvador Dalí's painting 'The Persistence of Memory' attached to the wood, wiggling up the door like a caterpillar.

Make it bizarre. If your first location is a tree, don't just imagine a clock by its trunk, add action. The clock can grow from the tree like giant fruit and swing back and forth, or fly from its branches like a bird.

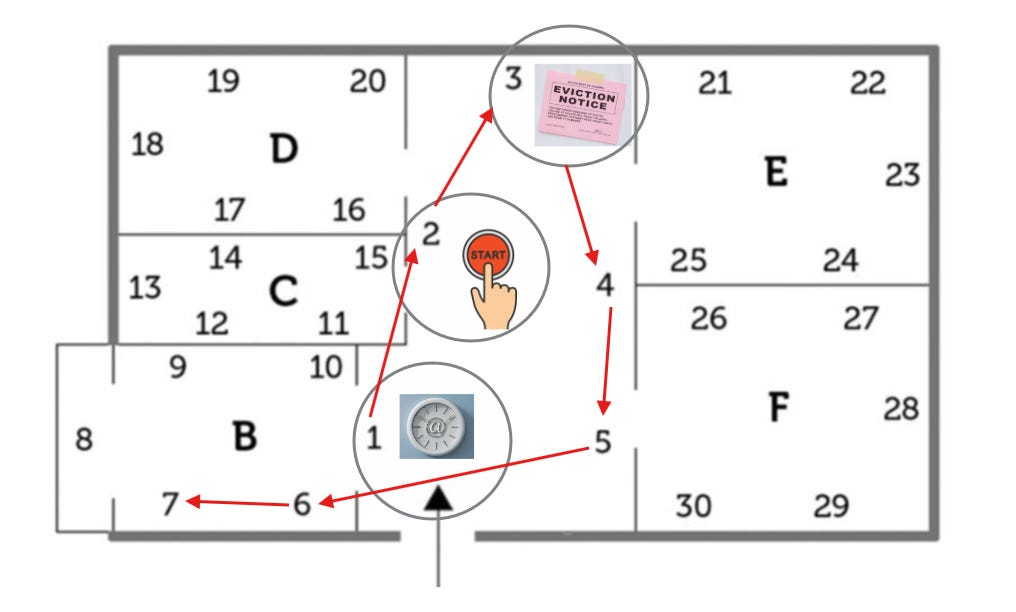

Continue steps 1-4 for all 7 phrases.

Now that you have encoded “at the same time” at your first location, continue this process for the other phrases and store them in locations 2-7.

In early memory treatises, rhetoricians intentionally limited their examples, believing this would help readers to actively practice the mnemonic techniques. For they argued that the very act of creating an image strengthens your ability to recall it later. Here are a few more examples to model after,

“At the same time” = a clock

“Great start” = a red start button

“I noticed” = an eviction notice

According to neuroscientists, our brains are naturally wired for spatial navigation, which is why memory palaces work so well. In order to access these phrases in the future, you can simply navigate to your memory palace, and see each image in its designated locus with your “mental eye” (oculus mentis).

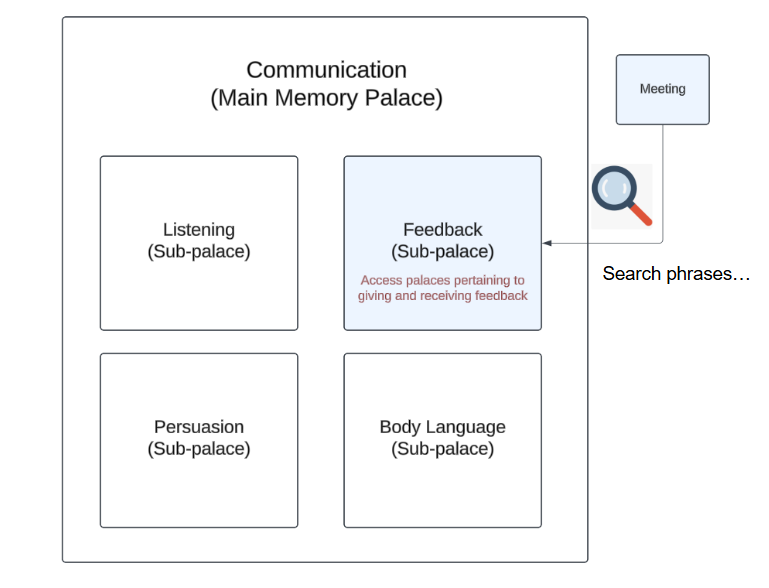

PART II. A Mental Framework: On Recovering a Designed Memory

Before the Google search bar and LLM’s, there was the ars memoria. Ancient rhetoricians talked about a designed memory, that is, memory deliberately structured for use. In classical education, memory was a canon of rhetoric, a tool for composition. This is why inventory and invention are so closely related. Both come from the Latin root meaning "to find" (“invenire”). When composing, the rhetorician searched their internal storehouse of memorized texts to create something new: lectures, legal arguments, sermons. You invented by finding and recombining what you already possessed.

Think of it as a hierarchical database: you can build a main memory palace (“Communication”) that contains nested sub-palaces (feedback, persuasion, listening, body language, etc.), each storing relevant quotations, articles, and contextual advice you can query on demand. So, when you are in a meeting and need to compose feedback, you can systematically search your internal storehouse just as the ancient rhetoricians did in order to craft a thoughtful response.

There are times when you can't pull out your phone to search for that great article you once read. There are times when you need to be quick on your feet and adapt your approach on the spot. Imagine sitting in a one-on-one with one of your direct reports where you need to address a concern. You're reading the room, and the conversation is getting rather tense. Twenty minutes later, he's leaning forward, thanking you for the thoughtful feedback you gave and expressing gratitude for the way you demonstrate care.

If you found this post helpful, please consider showing your support by:

Becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Leaving a like and/or comment

Restacking this post or restacking with a note.

Subscribe now for memory techniques spanning the Classical, Medieval, Renaissance, Modern, and Contemporary periods made practical for today.

Thanks for reading!