Dante and the Mnemonic Text: The Memory Arts Tradition in the Divine Comedy

Imagery, Poetic Meter and the Proper Use of Space

Ezra Pound once remarked, “Dante wrote his poems to make people think.” So, here is a thought to consider: What is the role of memory in the Comedy? As I argued in another post, considering Dante’s literary influences and educational background, he would have certainly been trained in rhetoric and mnemonic principles from the fourth canon. What we see is that Divine Comedy is not like a memory palace, it is one. He invites us to walk with him and journey through places/loci. As Hollander observed,

“The grammatical solecism (‘Midway in the journey of our life, I came to myself…]"), mixing plural and singular first-persons is another sign of the poet’s desire to make his reader grasp the relation between the individual and the universal, between Dante and all humankind. His voyage is meant to be understood as ours as well.”

The Proper Use of Space

What we see is how Dante incorporated elements of the memory arts tradition into the way he thought about poetry. Ancient rhetoricians taught their students in meticulous detail on how to design loci to aid recollection in one’s memory palace (See How to Build a Memory Palace). Images should not be too large or too small. The space between each locus should be about a wingspan. Loci must contain variation and easily distinguished from one another as to prevent confusion. The classic text Ad Herennium suggested to form loci in unfrequented places in order to strengthen impressions. As Thomas Bradwardine (c. 1300-1349) noted in On Acquiring a Trained Memory,

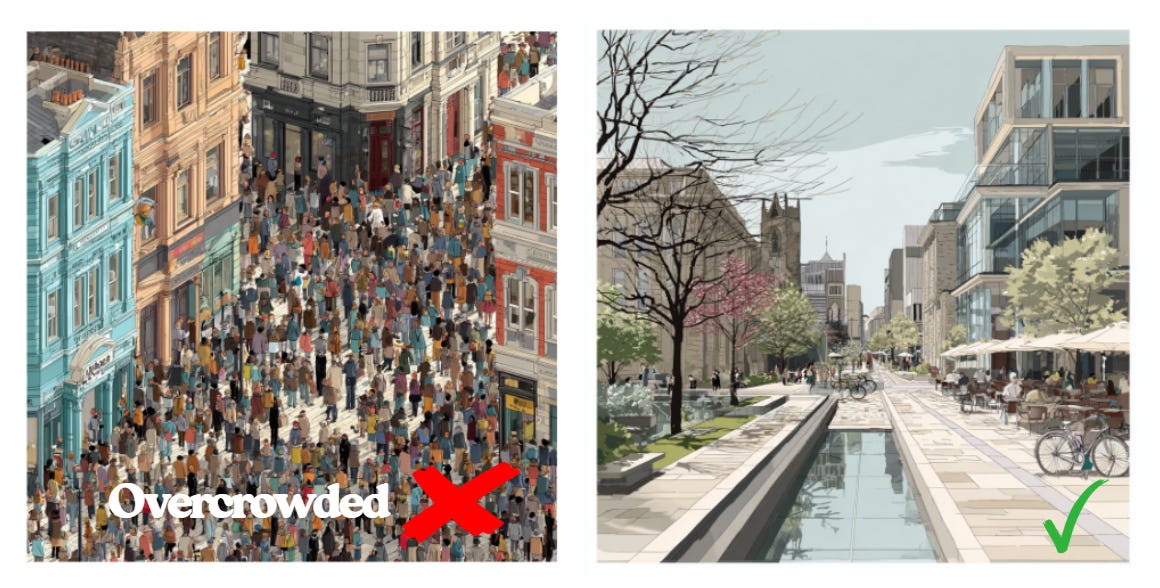

“…your backgrounds should not be made in a crowded place, such as a church, the market, and so forth, because the images of the things crowding such places, which would occur in a crowd in your memory, may block other images of things that you intend to place there” (trans. Carruthers).

In other words, when choosing a place to be used as a memory palace, it is recommended to avoid places that are busy with people and action. In order to avoid confusion during recall our loci should not be overcrowded. We should construct memoryspace in such a way that what we intend to memorize is readily accessible to the mental eye and the mnemonic image is the primary focus.

The Regularity of Tercets

From a structural standpoint, Dante designed the Divine Comedy in such a way that it can be memorized with only 1-3 images per line. This provides the perfect amount of space for images in a locus and helps avoid overcrowding in one’s memory palace. The poem maintains strict consistency and is set in hendecasyllabic verse rather than vers libre or variable foot. This regularity is deliberate. Each tercet contains exactly 33 syllables (11 + 11 + 11), symbolically representing the Trinity. This consistency of line-length makes the process of memorization less challenging. Notice how he structures Inferno 1.1-6,

“Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

ché la diritta via era smarrita. 3

Ahi quanto a dir qual era è cosa dura

esta selva selvaggia e aspra e forte

che nel pensier rinova la paura! 6”

Additionally, when approaching the memorization a text, rhetoricians made a distinction between two types of artificial memory: 1) memoria rerum (“memory of things”) and 2) memoria verborum (“memory of words”). As the author of Ad Herrenium stated,

“Rules for images now begin, the first of which is that there are two kinds of images, one for ‘things’ [res], the other for ‘words’ [verba]. That is to say ‘memory of things’ makes images to remind of an argument, a notion, or a ‘thing’; but ‘memory of words’ has to find images to remind of every single word.”

What we notice is that Dante’s combination of striking language and choice of poetic meter makes it easy for the reader to achieve both memoria rerum and veborum. One can divide each line into smaller chunks and create images from just a couple of key words and phrases such as cammin/vita, mi ritrovai/selva, diritta/smaritta, and so on. By virtue of this quality, one could store one line per locus which allows for quick access to specific points in one’s internal storehouse. Dante composes with intention and the art of memory in mind.

Dante, Our Guide through the Realm of Texts

The Divine Comedy also uses another mnemonic device popular in the Middle Ages: rhyme. Medieval monks used rhymes to memorize library catalogues. Alexandre de Villedieu known for his work Doctrinale, used 4,000 rhymed hexameters to outline the rules of Latin grammar. Similarly, in the original Italian text, Dante’s uses rhyme, the terza rima (ABA BCB CDC), a scheme which contributes to the poem’s sense of forward motion.

I think this rhyme scheme is directly tied to the method-of-loci process. For one of the most crucial aspects of the memory palace technique is knowing how to navigate through imagined space, that is, knowing the position of your next locus. This is precisely why contemporary memory experts such as Andrea Muzii advises his students to design memory palaces with intuitive directionality. A common mistake in memory sports is skipping loci during recall, an error often attributed to poor palace design. But the Comedy is not poorly designed; rather, one encounters masterful craftsmanship.

He rescues us from forgetfulness as he thoughtfully aids our memory for when we have lost our place. Dante the poet, as Virgil, “guides” our steps as it were through the realms of our memory palace. He does so through a rhyme scheme that continually hints at the image of the sequential locus. It is then in our familiarity with the text that we become accustomed to the fact that A in the 3rd position rhymes with A in the 1st position, and that B in the 6th position rhymes with B in the 4th position, and so on.

As

put it in the introduction to his translation of the Inferno,“He wanted a poem that was ‘in the head’ but also in the nerves and in the veins. It would be a lofty poetic journey toward the stars, but made with words that dig in, prick, and wound, words unforgettably memorable because gritty, haptic, and textured.”

The Comedy is not only a poem, but also a palace. Dante, the pilgrim invites us to journey with him through places by virtue of places. He calls us not to slumber, but to remember the beauty of virtue and the dangers of vice.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider showing your supporting by:

Becoming a free or paid subscriber

Leaving a like and/or comment

Restacking this post with a note.

Subscribe now to learn more about the history of artificial memory spanning from the Classical, Medieval, Renaissance, Modern, and Contemporary periods.

Thanks for reading!

Such a lovely passage on the ultimate goal of Dante's Inferno, and how Dante built the poem/story to help readers memorize it. I have not had the pleasure of studying Italian, yet when we traveled to Italy for my husband's teaching, I was able to read street signs and some Italian newspapers.

If you analyze Dante’s Italian, the 11+11+11 rule seems a little iffy, for he often counts two syllables as one if they are both vowels and ignores unstressed syllables if they fall at the end of the line.

By “images” you seem to mean any noun or modifying phrase even if they are abstract rather than concrete. Doesn’t that place an additional burden on memorization, when (contra the author of Ad Herrenium) it is so much more efficient to rely on muscle memory to remember the words, precisely for the reason you point out, the pairing (and indeed, wealth) of rhymes, alliteration and assonance?